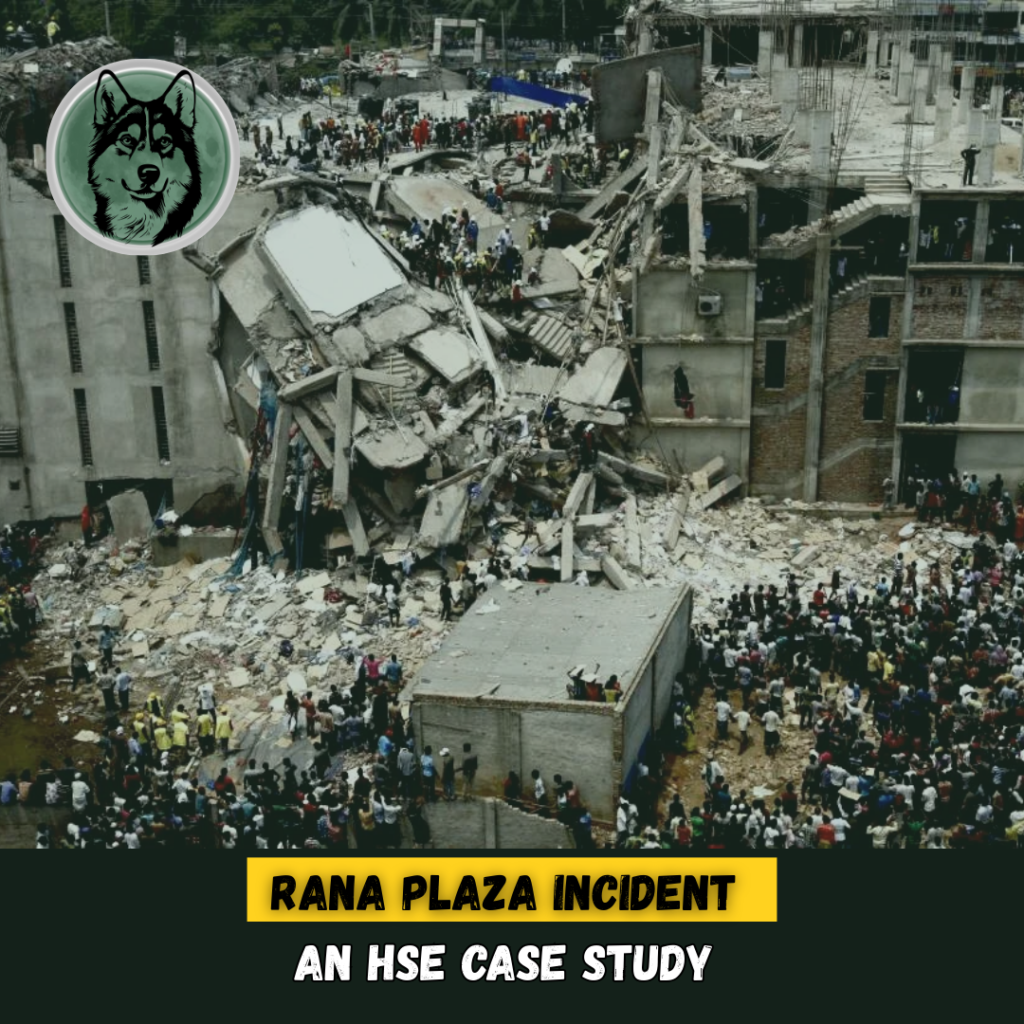

Introduction

The Rana Plaza collapse of 2013 stands as one of the deadliest industrial disasters in modern history and a defining failure of occupational health, safety, and governance. The incident clearly demonstrates how unsafe building design, weak regulatory oversight, and unethical management decisions can combine to create catastrophic risk. For HSE professionals, consultants, and trainers, Rana Plaza remains a critical case study on risk assessment, safety culture, and legal accountability.

Owner, Date, and Location

Rana Plaza was owned by Sohel Rana, a politically influential businessman in Bangladesh. The building collapsed on 24 April 2013 in Savar, an industrial area near Dhaka. At the time of the incident, the complex housed multiple garment factories supplying international clothing brands.

Building Facility and Design Conditions

The structure was originally approved for commercial use but was later converted into an industrial facility without proper engineering approval. This change significantly increased structural risk. Key facility and design failures included unauthorized additional floors beyond approved limits, installation of heavy industrial sewing machinery, placement of large diesel generators on upper floors, and non-compliance with building and fire safety regulations. These conditions made the building structurally unfit for industrial operations, particularly those involving continuous vibration.

What Happened?

On 23 April 2013, visible cracks appeared in the building, prompting engineers and authorities to declare it unsafe and recommend immediate evacuation. While commercial offices closed, garment factory workers were ordered to return to work the following day. On the morning of 24 April, a power outage led to the operation of diesel generators. The resulting vibration caused progressive structural failure, and the building collapsed completely within minutes.

Why This Incident Is Considered the Deadliest of the Decades

The Rana Plaza collapse is regarded as the deadliest garment-industry disaster due to its scale, preventability, and global impact. Approximately 1,134 workers lost their lives, while more than 2,500 people were injured, many suffering permanent disabilities. Clear warning signs were ignored, and the tragedy triggered major global reforms in garment-sector safety. No other modern industrial accident in the sector has resulted in such a high number of fatalities in a single event.

Loss Assessment from an HSE Perspective

Human losses included large-scale loss of life, permanent disabilities, and long-term psychological trauma among survivors and families. Economic and organizational losses involved factory shutdowns, production delays, compensation payments, legal penalties, and increased compliance costs. Reputational losses extended beyond individual companies, damaging national credibility and reducing international buyer confidence in supply chains.

Incident Investigation Using the Fishbone Model

A fishbone (Ishikawa) analysis shows that the collapse resulted from multiple interconnected failures rather than a single cause. Management prioritized production pressure over worker safety. Engineering failures included illegal construction and poor structural design. Machinery-related vibration from generators worsened instability. Workers lacked authority to refuse unsafe work. Regulatory bodies failed to enforce inspections and compliance. The root cause was a systemic breakdown of safety governance.

Incident Investigation Using the Bow-Tie Model

The top event was the structural collapse of the building. Key threats included unauthorized structural modifications, excessive loading and vibration, ignored safety warnings, and the absence of formal risk assessments. Preventive controls such as independent structural audits, enforcement of evacuation orders, and worker stop-work authority were either absent or failed. Consequences included mass casualties, economic disruption, legal action, and international criticism of supply-chain practices. Post-incident mitigation involved emergency rescue operations, medical treatment, compensation schemes, and industry-wide safety agreements.

How the Incident Could Have Been Managed

From an HSE professional’s perspective, the Rana Plaza disaster was entirely preventable. Fitness-for-purpose building design, independent structural audits, empowered workers with stop-work authority, formal risk assessments, and strong regulatory enforcement could have broken the chain of failure long before the collapse occurred.

Key Lessons for HSE Professionals

Safety culture must always override production pressure. Structural integrity is a core HSE responsibility, not just an engineering concern. Early warning signs must trigger immediate action, not negotiation. Strong legal enforcement and ethical leadership are essential for sustainable safety management.

Final Lesson: The Importance of Safety

The Rana Plaza tragedy reinforces a fundamental truth of occupational health and safety: safety must never be compromised for productivity or profit. The risks were visible, the warnings were clear, and prevention was possible. Failure to act turned manageable hazards into a catastrophic disaster. Effective safety management is proactive, ethical, and leadership-driven. When human life is placed at the center of decision-making and accountability is enforced, workplaces become safer, operations become sustainable, and tragedies like Rana Plaza can be prevented rather than repeated.